EUROPEAN FUNDS ARE THE NEW ‘GOLD FOR BRAZIL’, WHICH ACCELERATES ITS WEAK PORTUGUESE ECONOMY

By Pedro Araújo / Jornal de Noticias

Agriculture is eclipsed and services are booming. Successful industries are few. The Portuguese are poorer in relative terms, despite the millions in Brussels.

“The long-term trend, for more than two decades, has been to become poorer and poorer in relation to the other European Union (EU) states. The purchasing power of the Portuguese is now much lower than that of most other EU countries,” says Nuno Palma, professor of economics at the University of Manchester. Half a century of democracy has not translated into prosperity, despite the millions the country has received from Brussels since joining the then EEC on June 12, 1985.

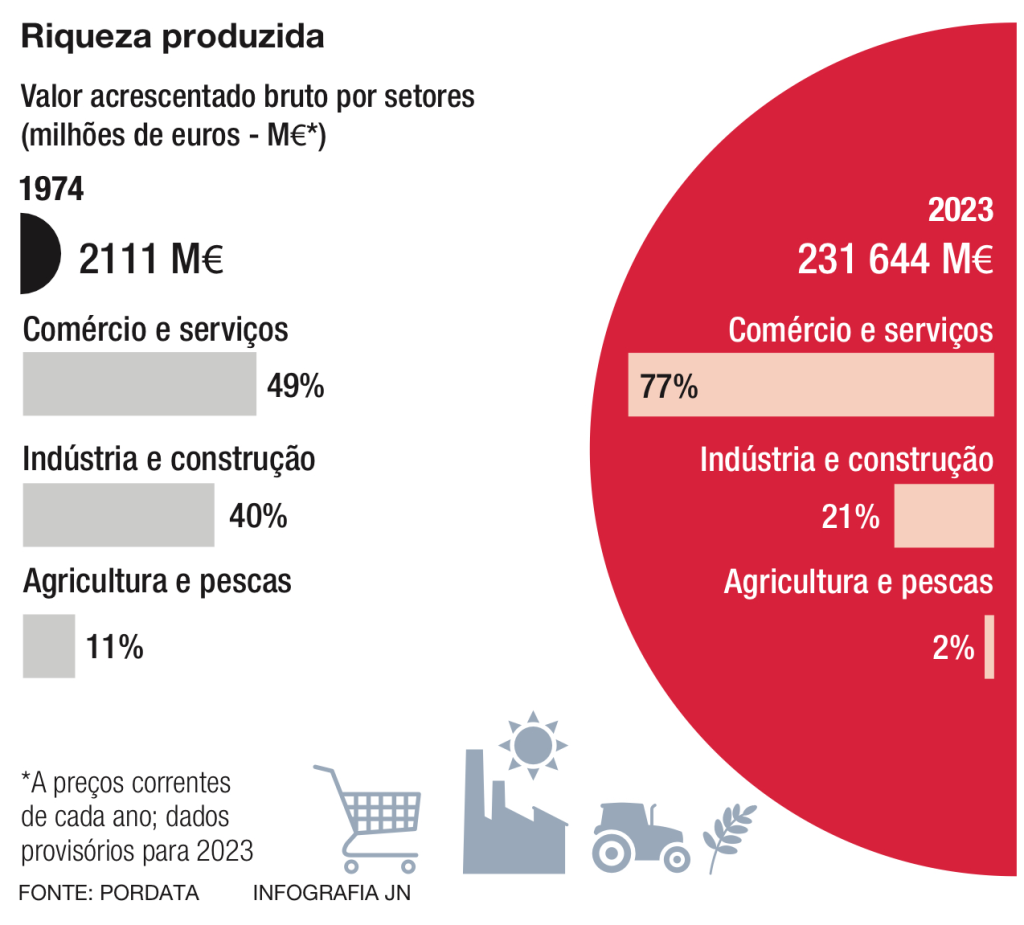

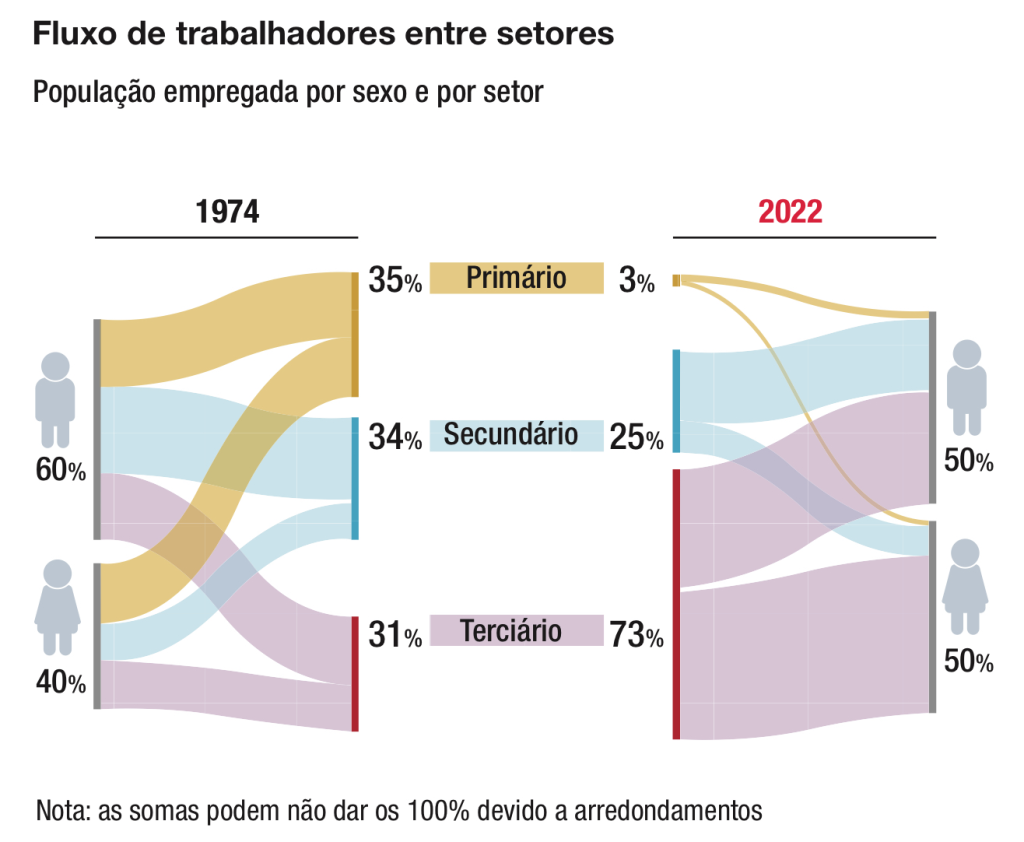

In 1974, the year of the April 25 Revolution, agriculture and fishing accounted for 11% of the economy and today they account for only 2%. The concentration of commerce and services increased from 49% to 77%. Industry and construction have halved and now account for 21% of GDP. What remains is the strength of footwear – the sector’s exports have grown by 54,533.33% in value since 1974 – and textiles, the robustness of metallurgy and Autoeuropa as a reference point for foreign investment.

NEW STATE

Ideological prejudices aside, the 50 years of democracy have hardly surpassed the previous decades. “They were almost 30 years of uninterrupted expansion, in which the economy did not simply keep pace with the most developed ones. Portugal was then one of the fastest growing countries in the world, along with Spain and the so-called Asian tigers,” says Professor Luciano Amaral in his book “Economia Portuguesa”.

In his book “As causas do atraso português” (The causes of Portuguese backwardness), recently published in Portugal, Nuno Palma corroborates this idea: “The convergence with the richest Europe started in the early 1950s was interrupted for a decade after April 25,” he points out. Convergence then resumed, but Nuno Valério acknowledges that “the last quarter of the 20th century was much more dynamic than the first quarter of the 21st century.”

The result of the change in the profile of the economy is not without its critics, despite the successes achieved. “We may need state intervention and a (collective) strategy to guide it. And arguably, after decolonization and European integration, there has been too much short-term emergence. Perhaps the lessons of the pandemic and the exigencies of geostrategic conflicts and climate change will help to overcome it,” says Nuno Valério, ISEG professor and specialist in the history and theory of economic development.

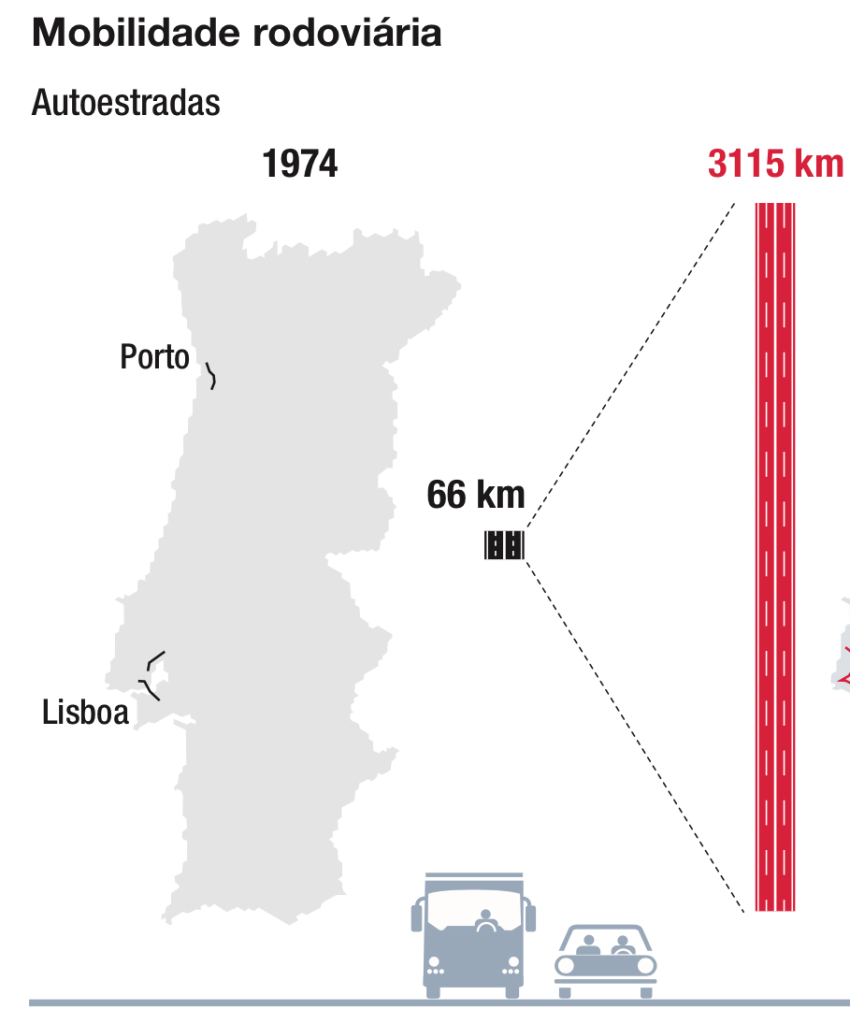

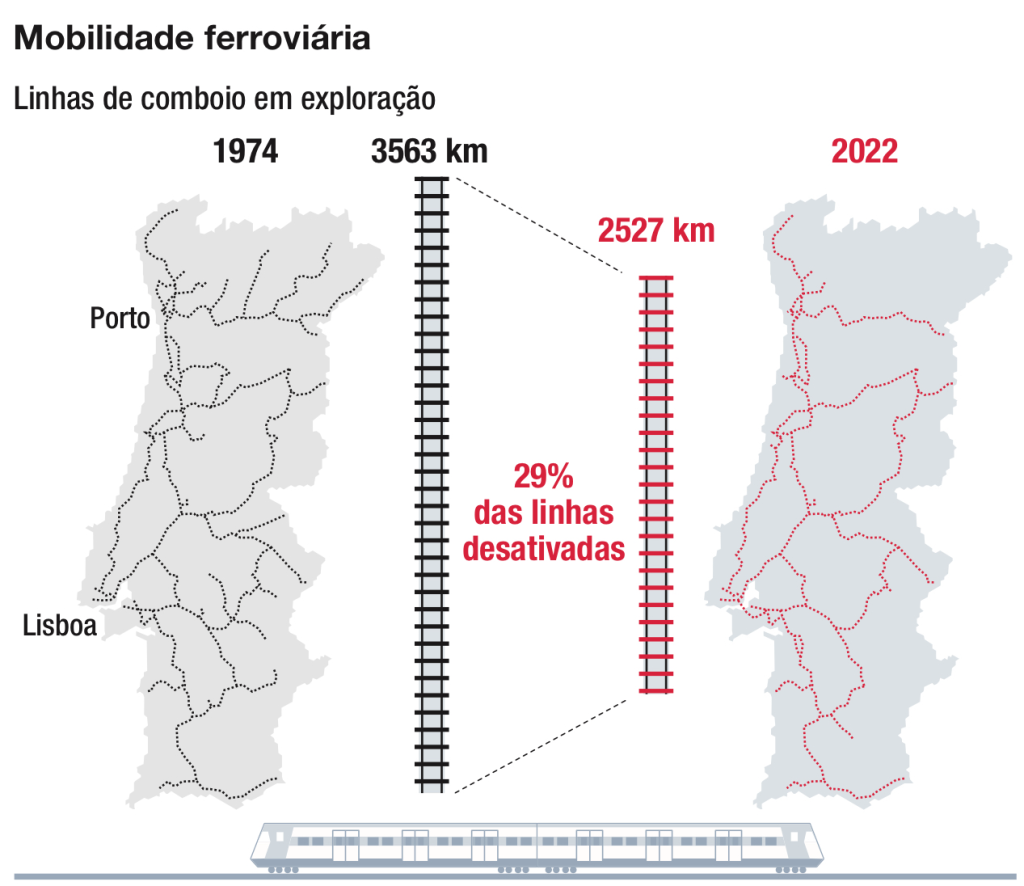

But what has become of the millions of European funds? The number of kilometers of highway today is 47 times greater than in 1974. This is a visible effect. The money received from Brussels represents about 3% of the annual GDP since accession to the EEC, the equivalent of two Autoeuropas per year.

The problem of gold from Brazil, which arrived in Portugal in large quantities in the 18th century and did not develop the metropolis, is repeated. “The people have to feel in their pockets the consequences of bad government (…). European aid is an aspirin or a band-aid,” reads Nuno Palma’s book. The Manchester-based academic even advocates abolishing the funds to expose the wrong decisions of the political class and predicts that Portugal could be the poorest country in the EU within a decade.

Nuno Valério’s opinion differs from that of Nuno Palma: “I don’t agree with the main thrust of the argument, although I am far from thinking that the funds have always been well used.”

Miguel St Aubyn, professor at ISEG, believes that “the possible lack of vision and strategy of the political class lies in the fact that the country has not known how to take advantage of its opportunities, and the European funds are only part of the problem”.

CHALLENGES FOR THE FUTURE

Rather than merely reflecting on the past, Miguel St Aubyn, ISEG professor and member of the Public Finance Council, identifies six challenges for the next 50 years.

More and better investment

To grow sustainably and for Portugal to converge in productivity and per capita income, investment must increase and be of better quality. This is as true in the public sector and infrastructure as it is in the private economy. We need structural, diversified investments, based on knowledge and skilled labor, and that favor an efficient energy and environmental transition.

Less inequality

We are still a deeply unequal country and we find it hard to accept. Inequality is not only an injustice, it is also an economic waste. Reducing it as a clearly identified objective has implications for the design of public policies as a whole.

Improving housing

Housing conditions are poor. Responses to this problem should have begun yesterday, and while urgent, the effects are slow to be felt. Market failures make public intervention in supply, regulation and incentives necessary.

Attracting and retaining qualified young people

Although it attracts a new immigrant population seeking a better life here, the truth is that many qualified young Portuguese end up seeking and finding more rewarding jobs in foreign countries, namely in the European Union, the United Kingdom or the United States. Along with the declining birth rate and increasing life expectancy, the population is gradually aging.

A commitment to growth and innovation

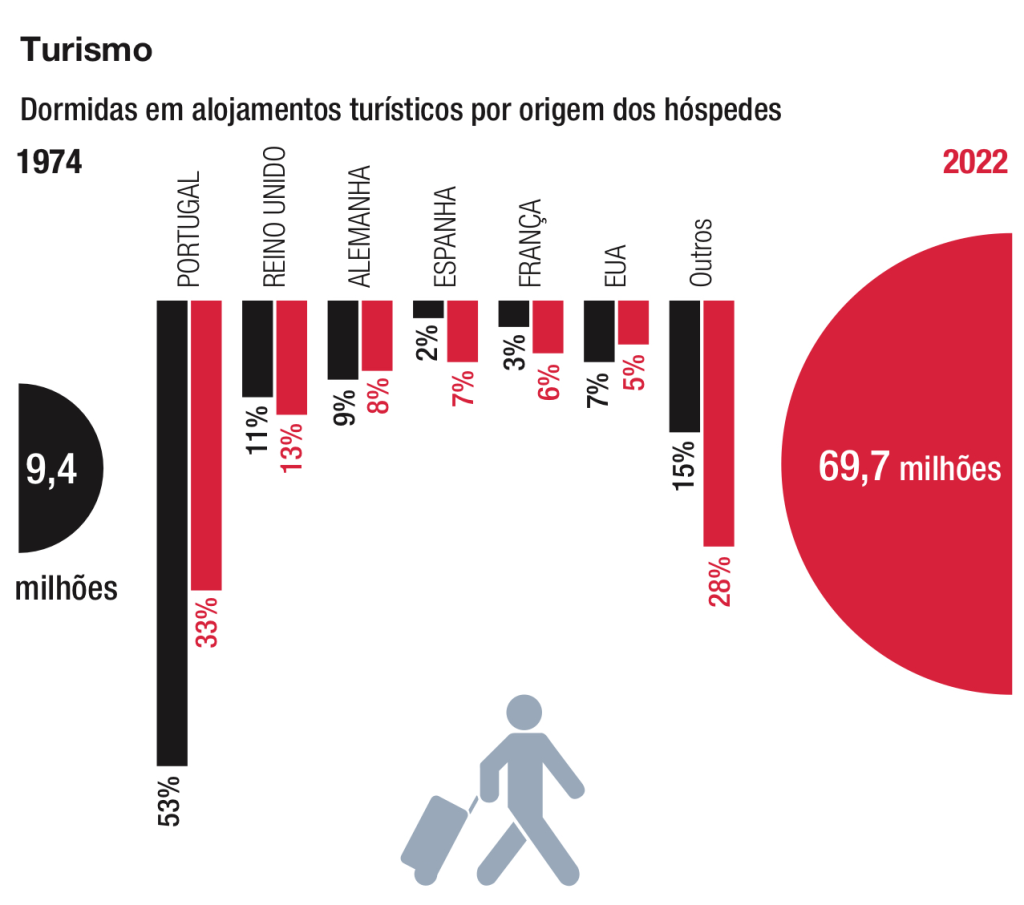

Tourism and related activities have been an important driver of the Portuguese economy. For other sectors to develop, where productivity gains from technological innovation are more significant, it is important that the labor force is increasingly skilled, open-minded and capable of innovation.

Reform of the State

The reform of the aging public administration is one of the major challenges of the coming years. It will involve reorienting the focus of policies from the short to the medium and long term and the necessary systematic evaluation. The implementation of a spending review system, and also of taxation, can be extremely important to increase efficiency and thus widen the budgetary margin to meet new challenges (environmental transition or reinforcement of the NHS).

MAJOR CRISES OF DEMOCRACY

1983-85

In 1979, the world economy suffered an oil crisis and the Portuguese crisis manifested itself in the following years. The government asked the IMF for help (1983-1985), as it had already done in 1977-78.

1992-93

In 1990 the first Gulf War broke out, with the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq, which provoked an armed intervention led by the United States. Portugal felt the recession in the following years.

2002-03

The country had joined the euro in 1999. It was a time of cheap money for both households and the state. Debt skyrocketed and Durão Barroso, elected Prime Minister, said that “the country is on its ass”.

2008-09

The international financial crisis originated in the United States, with problems with home loans. Unemployment soared, credit became more expensive and the economy came to a standstill.

2010-14

It became known as the sovereign debt crisis and Portugal was not immune. Troika intervention (2011-2014) left a mark and bad memories.

2020-21

The crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic was global. Tourism became almost unviable and so did Europe-Asia trade. Economies contracted.

————

PEDRO ARAÚJO is the deputy executive editor of Jornal de Noticias.

This article was originally published in Portuguese in Jornal de Noticias, with whose permission we reproduce it here. If used, please cite the author and the newspaper.